Find Workers

⌄

The goods-based economy has undergone some big swings lately, from the enormous surge in demand during the stay-at-home phase of the pandemic to the stagnation that resulted when consumers' spending shifted into services last year. Now, with inventories finally clearing up, the supply chain is poised to get moving again. So where is the need for labor most acute?

Earlier this year, our State of Warehouse Labor report found that businesses expected to have an easier time attracting and retaining workers in 2023 versus 2022. Their staffing strategies were relying less on increases in pay and more on offering flexible schedules and other benefits. But the situation may not be quite as rosy everywhere in the supply chain.

Looking across the economy, it's possible that logistics businesses actually overhired last year. Many were expecting that demand would continue at the high levels of 2020 and 2021, when people were mainly spending their money on goods delivered to their homes. But that's not what happened; services took over most of the growth in spending. So if we compare actual employment in transportation and warehousing. For those seeking opportunities, Temp Staffing and Workers in Trenton | Instawork can provide valuable insights into the current job market.

Looking across the economy, it's possible that logistics businesses actually overhired last year. Many were expecting that demand would continue at the high levels of 2020 and 2021, when people were mainly spending their money on goods delivered to their homes. But that's not what happened; services took over most of the growth in spending. So if we compare actual employment in transportation and warehousing to the level that spending on goods (adjusted for inflation) would have predicted, the graph looks like this:

For much of 2020 and 2021, logistics businesses were playing catch-up as spending on goods predicted much higher levels of employment. By early 2022, they had closed the gap but they kept hiring. As a result, they overshot. Yet many businesses held onto their employees, even if they had less work to do, for fear of needing to rehire when demand picked up again. And now, with a record back-to-school season expected, the predicted level of employment is once again above the actual.

Meanwhile, the story is a little different in manufacturing. At the production end of the supply chain, the gap between actual and predicted employment never closed:

The gap did shrink until late 2022, but then manufacturing firms stopped hiring either out of caution, or because they could no longer find enough employees in a tight labor market. Either way, the sector still looks short by almost half a million workers.

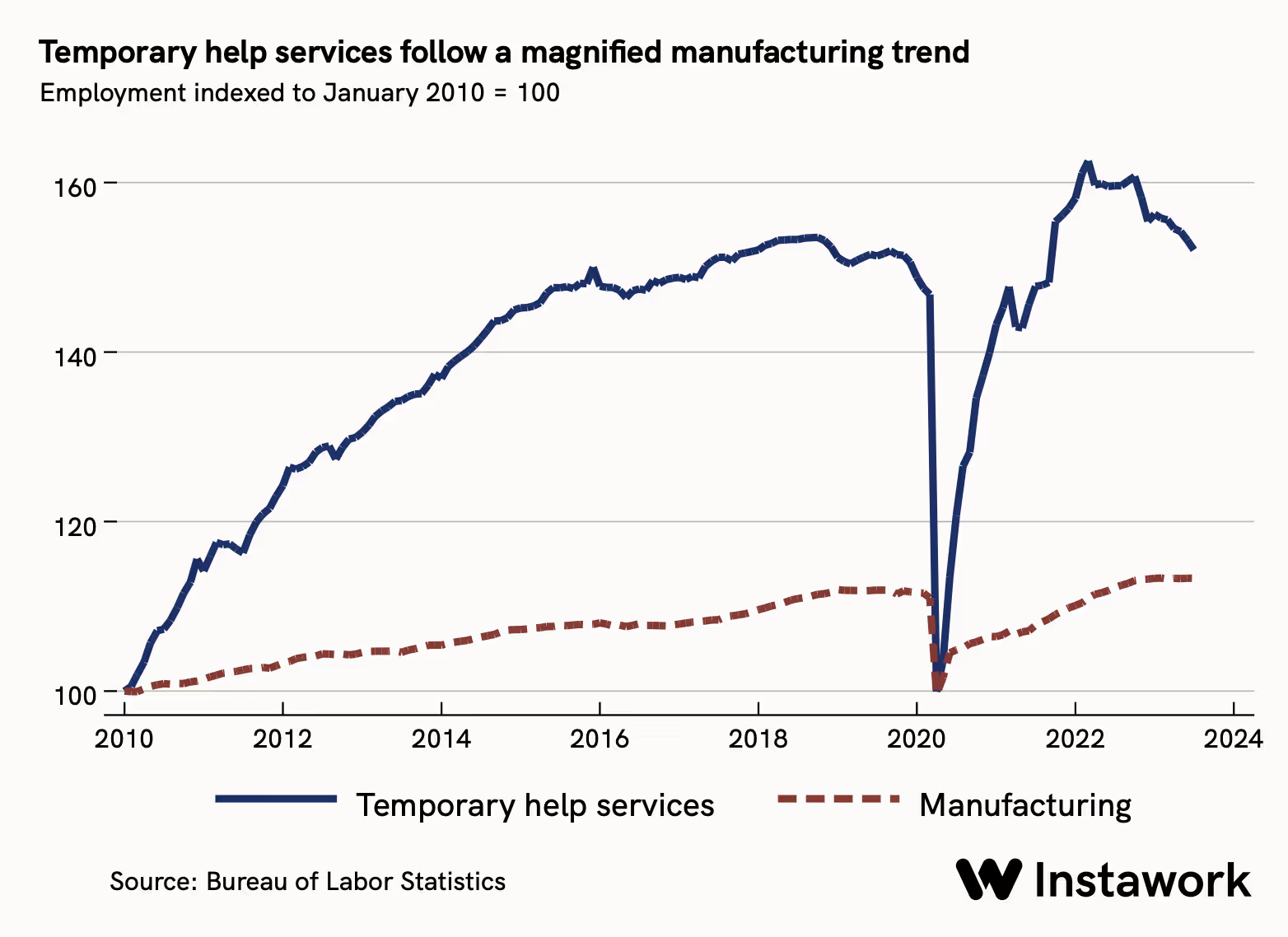

In situations of economic uncertainty, businesses in the supply chain often resort to temp agencies for help. In fact, agency-provided workers for production and logistics roles account for about 45% of the "temporary help services" category in government statistics. Naturally, the trend has a much broader amplitude than the trend for wage and salary workers in manufacturing:

Because workers from temp agencies are often "last in, first out" that is to say, used at the margin some data watchers interpret a decline in their employment as an early sign of recession. Yet it's not clear that the economy was heading into recession in 2018 or 2019, before the pandemic. Nor does the economy appear to be in recession now.

So what's actually happening? For one thing, businesses may be hiring workers from temp agencies or replacing them with other permanent employees. Indeed, because the labor market is still so tight, people who might have worked for temp agencies may now be finding permanent positions. The dip could be a question of supply as much or more as of demand.

This doesn't mean that businesses have run out of options. In fact, they could have navigated the past couple of years more easily as well as being in a better position now if they had used workers with more flexibility.

Our most forward-thinking partners typically post a recurring set of shifts for experienced professionals who are not employees but who are tested and trusted in their roles. These professionals determine their own schedules, but there are always enough of them on a business's roster to fill the shifts. They often have other jobs, as our Monthly Labor Market Report shows, but they still want extra work.

These recurring workers can offer businesses more flexibility than permanent employees without harming productivity. They also represent a talent pool that may not be accessible to businesses that only use temp agencies. Best of all, they can fill shifts extremely quickly. On our platform, the average time to fill light industrial shifts has been under 12 hours all year and is now around four hours for the most popular roles:

Even if the supply chain is running out of workers to hire, there's another labor pool eager to step in. And as the goods-based economy heats up, these professionals can step in to replace overtime shifts and prevent downtime by covering for employees who take time off. Now is the time to start building a roster of trusted Pros the best prepared businesses will be the ones who can use every staffing option available.

These metrics, derived from data aggregated across the Instawork platform, compare the two weeks starting 8/3/2023 to the previous two weeks. To control for the overall growth of the Instawork marketplace, only shifts involving businesses that booked shifts in both periods are included:

To receive future briefings and data insights from our Economic Research team, please subscribe below. Follow daniel altman on Twitter at @AltmanEcon or on LinkedIn.